US District Court Southern District of New York 7 september 2012, 12 Civ. 00201 (AJN) (The Velvet Underground tegen The Andy Warhol Foundation)

Een samenvatting en analyse van Margriet Koedooder, De Vos & Partners Advocaten N.V..

Een samenvatting en analyse van Margriet Koedooder, De Vos & Partners Advocaten N.V..

In steekwoorden: Auteursrecht. (niet-ingeschreven) merkenrecht. Licenties voor hergebruik. Gratis artwork. Stichting als erfgenaam. Onthoudingsverklaring met ruime omschrijving. Doorwerking van rechtspraak in de praktijk. Negatieve verklaring voor recht. Naar Nederlands recht.

Op 9 september is door de Amerikaanse District Court of New York uitspraak gedaan in een door de Velvet Underground (hierna ook: ‘de band’) tegen de Andy Warhol Foundation (hierna: AWF) aangespannen procedure. De procedure handelt over een wereldwijd bekende illustratie die Andy Warhol van een banaan heeft gemaakt. Dat was in 1967, toen de Velvet Underground haar baanbrekende eerste album uitbracht, getiteld The Velvet Underground & Nico, ook wel ‘ The Banana Album’ genoemd. Alhoewel de band destijds nooit enig commercieel succes heeft gekend, geldt de Velvet Underground wel als één van de belangrijkste muzikale invloeden voor alternatieve rockbands. Warhol verklaarde in 1966 dat hij een sponsor was van de band en ontwierp vervolgens gratis het artwork voor het album, te weten een grote gele banaan met daarbij een gestileerde handtekening van Andy Warhol. In het vonnis wordt overigens, ondanks deze handtekening, uitdrukkelijk opgemerkt dat op het album een ‘ copyright notice’ met de naam van Andy Warhol ontbreekt.

De band viel uit elkaar in 1972, maar hield in 1993 nog eenmalig een allerlaatste ‘ European Reunion Tour’. Ook Paradiso in Amsterdam werd op 8 juni 1993 bezocht in het kader van de tour, en schrijver dezes mocht daarbij aanwezig zijn. Het was de allereerste keer ooit dat bezoekers van Paradiso maar liefst honderd gulden moesten neertellen voor een optreden, dat immers uniek was. Ook een zwart t-shirt met daarop de beruchte banaan is sindsdien in mijn bezit. Alhoewel er dus wel degelijk merchandisingsartikelen met de banaan zijn verkocht na 1972 en er reclame is gemaakt met de bananenprint, bleek de allerlaatste licentie van de band te dateren uit 2001: een advertentie voor het merk Absolut Vodka.

In 2009 had de Andy Warhol Foundation (hierna: AWF) een brief gezonden aan de band, waarin werd aangegeven dat zij meende dat de band inbreuk maakte op het auteursrecht van de stichting op de bananenprint. De Velvet Underground betwistte daarop de aanspraak van AWF op een auteursrecht en beriep zich op haar beurt op een eigen merk, waarvan echter de geldigheid door de stichting werd betwist. In het vonnis wordt een paar keer opgemerkt dat volgens de band sprake is van een bananenontwerp met ‘secundary meaning as VU’s mark’. De band heeft dus geen ingeschreven merkrecht. Ik begrijp dat het hierbij gaat om:

‘A doctrine of trademark law that provides that protection is afforded to the user of an otherwise unprotectable mark when the mark, through advertising or other exposure, has come to signify that an item is produced or sponsored by that user.’

Medio 2011 krijgt de band er via een blogartikel in The New York Times lucht van dat AWF van plan is toestemming te geven voor het afdrukken van het bananenlogo en drie andere Andy Warhol prints op iPhone en iPad hoesjes. De band klimt vervolgens in januari 2012 in de pen en verzoekt AWF, dat nog steeds een auteursrecht claimt op de tekening, het gebruik ervan te staken. Aanvankelijk stelt de band zich daarbij op het standpunt dat AWF niet over een auteursrecht kán beschikken aangezien het ontwerp zich bevindt in het publieke domein. Andy Warhol heeft de banaan in 1966 namelijk aangetroffen in een advertentie, welke zich in 1966 al in het publieke domein bevond. Het ontwerp is in 1967 bovendien zonder ‘ copyright notice’ verschenen, aldus de band. In 1966 claimt dan ook niemand een auteursrecht op het ontwerp en ook daardoor bevindt het ontwerp zich in het publieke domein. Het ‘publieke domein’ argument is overigens in latere versies van de rechtsvordering van Velvet Underground geschrapt en blijkt niet meer uit het vonnis, maar het argument is er wel de oorzaak van dat AWF op de gedachte komt dat de band dan mogelijk geen rechtens te respecteren belang meer heeft bij de door haar verlangde verklaring voor recht. De band blijft zich intussen beroepen op het feit dat zij het bananenlogo gedurende tenminste 25 jaar voortdurend en onafgebroken heeft gebruikt als merk. Het ontwerp betreft zelfs een icoon, dat door het publiek wordt opgevat als toebehorende aan Velvet Underground.

De band heeft uitgerekend dat AWF jaarlijks tenminste 2,5 miljoen dollar verdient aan het verstrekken van licenties met Andy Warhol prints en dient naast een verzoek om een (negatief gestelde) verklaring voor recht, te weten dat AWF geen auteursrecht heeft op het ontwerp, tevens een financiële claim in bij de rechter. De rechter wijst de vorderingen van de band echter allemaal af.

AWF voert verweer. De band is al veertig jaar geleden uit elkaar gevallen dus heeft geen enkel recht van spreken meer volgens AWF. En juist door het beroep van de band op het publieke domein, althans door zich niet te beroepen op een eigen auteursrecht, heeft de band geen enkel rechtens te respecteren belang meer bij de verlangde verklaring voor recht. Daar komt bij dat AWF inmiddels een onthoudingsverklaring heeft getekend met daarin een ruime omschrijving:

‘ to refrain from making any claim(s) or demand(s), or from commencing, causing, or permitting to be prosecuted any action in law or equity’

De onthoudingsverklaring begunstigt zowel de band als een aantal daaraan gelieerde entiteiten. Kortom: in de optiek van de stichting ontbreekt er een juridisch relevant geschil aangezien AWF heeft verklaard nimmer te zullen procederen tegen partijen waarmee de band in heden, verleden of toekomst zaken doet met betrekking tot het bananenlogo.

De Amerikaanse rechter gaat daar in mee en stelt vast dat de zeer ruim gestelde onthoudingsverklaring met zich meebrengt dat van een juridisch relevant geschil met betrekking tot het auteursrecht op het bananen ontwerp geen enkele sprake (meer) is of kan zijn. Dat volgt uit de toepassing van de Amerikaanse Declatory Judgment Act (hierna: DJA). Er is geen concrete, daadwerkelijke (dreigende) schade meer aan te wijzen, terwijl abstracte discussies over het recht buiten het bereik van de DJA vallen. Deze wet is daar simpelweg niet voor bedoeld. De DJA staat niet toe dat een verklaring voor recht wordt verstrekt op basis van hypothetische feiten en standpunten. Het bananendispuut blijkt dus uiteindelijk een lege schil.

Of een onthoudingsverklaring inderdaad een juridische procedure kan blokkeren, hangt volgens de Amerikaanse rechter onder meer af van drie factoren:

- De reikwijdte van de verklaring: in dit geval breed;

- Heeft de onthoudingsverklaring wel of niet betrekking op zowel huidige als toekomstige gedragingen en producten: in deze zaak is dat zo;

- Bewijs ten aanzien van eventuele toekomstige inbreukmakende activiteiten: die zijn kennelijk niet aangetoond.

Vervolgens oordeelt de rechter over de vraag of er dan wellicht nog een actueel geschil aanwezig is tussen partijen. De band meent van wel, immers, de auteursrecht/merkenrecht controverse hangt nog boven partijen en de band claimt ook geld. Velvet Underground vreest met name dat haar toekomstige licentienemers t.z.t. alsnog met juridische acties van AWF geconfronteerd kunnen worden. De vraag is dan ook vooral of dergelijke mogelijke toekomstige gedragingen van AWF in de onthoudingsverklaring zijn gedekt. Dat is in feite een vraag van interpretatie van de tekst van de onthoudingsverklaring. Alhoewel de rechter géén declaratoir vonnis wil uitspreken, stelt de rechter in het vonnis wél vast dat de beperkte interpretatie van de band onjuist is. Ook eventuele toekomstige acties van AWF tegen licentienemers van de band vallen onder de onthoudingsverklaring, aldus de rechter. Grappig, hoe het oordeel van de Amerikaanse rechter dat een declaratoir vonnis niet kan worden gegeven, dan toch nog impliciet leidt tot het definitief vaststellen van een rechtsverhouding tussen partijen, te weten middels de uitleg van het contract.

Alhoewel de Velvet Underground haar rechtszaak formeel heeft verloren, heeft zij de strijd materieel wél gewonnen, immers AWF kan op geen enkele wijze meer optreden tegen licentienemers van de band. AWF heeft aan haar vermeende auteursrecht dus niets meer en licenties blijven voorbehouden aan de Velvet Underground.

Nederland

Hoe zit dat in Nederland? In het Nederlandse rechtstelsel is in artikel 3:302 BW bepaald dat de rechter ‘op vordering van een bij een rechtsverhouding onmiddellijk betrokken persoon’ omtrent die rechtsverhouding een verklaring van recht uitspreekt. In artikel 3:303 BW is vervolgens geregeld dat zonder voldoende belang, niemand een rechtsvordering toekomt. Uit de wetsgeschiedenis blijkt dat de categorie ‘onmiddellijk betrokken personen’ uit artikel 3:302 BW niet persé samenvallen met de in artikel 3:303 BW bedoelde personen die voldoende belang bij de rechtsvordering moeten hebben. Iemand die belang heeft bij een rechtsvordering is niet steeds een ‘onmiddellijk daarbij betrokken persoon’ en omgekeerd kan een onmiddellijk betrokken persoon niettemin geen belang hebben bij het instellen van een vordering. In welk geval deze persoon ook geen vordering toekomt (zie T&C bij artikel 3:302 en 3:303 BW).

De gevraagde verklaring voor recht kan zowel positief als negatief luiden: bepaald gedrag is juist wel of juist niet onrechtmatig. Een gevorderde verklaring voor recht strekt er toe tot het op jegens de bij die rechtsverhouding betrokkenen op bindende wijze vaststellen van het bestaan of preciseren van de inhoud van een rechtsverhouding. Vertalen we de Bananen-casus naar Nederlands recht, dan is de kans groot dat moet worden geoordeeld dat een declaratoir vonnis in beginsel mogelijk is vanwege het feit dat zowel de Velvet Underground, die een beroep doet op haar merkrecht als de AWF met haar beroep op het auteursrecht, aan te merken zijn als ‘onmiddellijk betrokken personen’. De gevorderde verklaring voor recht zou er dan toe kunnen strekken dat door de rechter voor partijen bindend wordt vastgesteld dat Velvet Underground bijv. over een (sterker) merkrecht op de Banenprint kan beschikken.

Of de Nederlandse rechter tevens zal oordelen dat de band - ondanks de onthoudingsverklaring - (nog steeds) voldoende belang heeft bij haar vordering valt echter niet goed te voorspellen. In dat geval zal de Haviltex-formule op de onthoudingsverklaring worden losgelaten, dan wel de letterlijke tekst meer tot uitgangspunt worden genomen, bijv. als de tekst van de onthoudingsverklaring in overleg tussen partijen, die zich daarbij lieten vertegenwoordigen door een advocaat, is opgesteld. Indien AWF dan tijdens de procedure niet bereid zou blijken haar voorgenomen licentie voor gebruik van het bananenlogo op iPad en iPhone hoesjes te staken, lijkt de kans dat AWF alsnog veroordeeld zou worden tot het staken en gestaakt houden van dergelijk toekomstig gedrag mij zeker niet ondenkbaar. Een verklaring om af te zien van een beroep op een bepaalde claim (auteursrecht op het logo) en zich te zullen onthouden van juridische acties tegenover de band en haar relaties, is m.i. iets anders dan een, liefst op straffe van een dwangsom, verklaring van de gedaagde partij dat bepaald voorgenomen, inbreuk makend gedrag alsnog achterwege zal blijven.

Margriet Koedooder

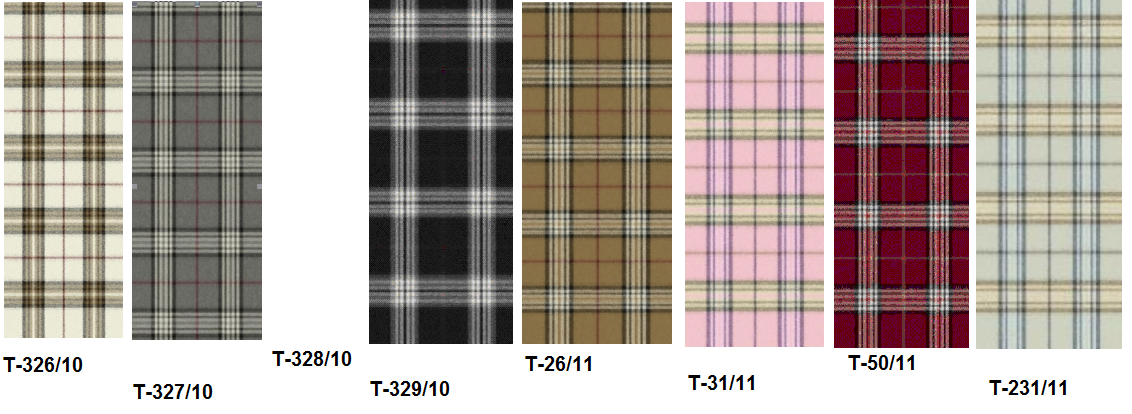

In't kort. Merkenrechtelijke bescherming van geruite afbeelding in diverse kleuren (klasse 18, 24 en 25: leer, weefstoffen en bekleding). Het Gerecht EU oordeelt, evenals de kamer(s) van beroep, dat de merken geen onderscheidend vermogen hebben. Vanuit een visueel oogpunt bezitten de tekens geen noemenswaardige afwijking ten opzichte van de weergave van soortgelijke, gebruikelijke en veel voorkomende patronen.

In't kort. Merkenrechtelijke bescherming van geruite afbeelding in diverse kleuren (klasse 18, 24 en 25: leer, weefstoffen en bekleding). Het Gerecht EU oordeelt, evenals de kamer(s) van beroep, dat de merken geen onderscheidend vermogen hebben. Vanuit een visueel oogpunt bezitten de tekens geen noemenswaardige afwijking ten opzichte van de weergave van soortgelijke, gebruikelijke en veel voorkomende patronen.

Domeinnaamrecht. Verwijzing naar WIPO bona fide refererend merkgebruik (Oki Data).

Domeinnaamrecht. Verwijzing naar WIPO bona fide refererend merkgebruik (Oki Data). Merkenrecht. Heraldieke elementen van het beeldmerk Swiss Sense met staatsembleem Zwitserland. Strijd met 6 ter, lid 1, sub a, van het Verdrag van Parijs. Misleiding geografische oorsprong. Ongeoorloofde concurrentie. Merkrecht inbreuk onvoldoende aangetoond. Misleidende reclame. Verwijzing naar esdoornbladarrest, zie

Merkenrecht. Heraldieke elementen van het beeldmerk Swiss Sense met staatsembleem Zwitserland. Strijd met 6 ter, lid 1, sub a, van het Verdrag van Parijs. Misleiding geografische oorsprong. Ongeoorloofde concurrentie. Merkrecht inbreuk onvoldoende aangetoond. Misleidende reclame. Verwijzing naar esdoornbladarrest, zie  Merkenrecht. We beperken ons tot een maandelijks overzicht van de oppositiebeslissingen van het BBIE. Vandaag heeft het BBIE een serie oppositiebeslissingen gepubliceerd die wellicht de moeite waard is om door te nemen. Zie voorgaand bericht in deze serie:

Merkenrecht. We beperken ons tot een maandelijks overzicht van de oppositiebeslissingen van het BBIE. Vandaag heeft het BBIE een serie oppositiebeslissingen gepubliceerd die wellicht de moeite waard is om door te nemen. Zie voorgaand bericht in deze serie:

Uitspraak ingezonden door Maarten Haak en Daan van Eek,

Uitspraak ingezonden door Maarten Haak en Daan van Eek,  Een samenvatting en analyse van Margriet Koedooder,

Een samenvatting en analyse van Margriet Koedooder,  In de

In de  Hogere voorziening na zaak

Hogere voorziening na zaak  Hogere voorziening na T-13/09 [red.

Hogere voorziening na T-13/09 [red.